26 Jan A Visit to the Sainsbury Centre

I think being asked to design a new museum or art gallery must be a plum commission for an architect as the chance to do something radical is almost expected. The Pompidou Centre in Paris or the Guggenheim in Bilbao are examples of buildings that have become iconic. I think the Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts in Norwich belongs in this company, but it is less celebrated, despite being every bit as ground-breaking when it was built in the early 1970’s. A year ago Jago Cooper became its Director, intending to be as radical with the collection as the building is architecturally.

A few years ago my husband directed a documentary for the BBC in which Jago told the sad story of the Rapa Nui people of Easter Island. As a result of this connection, we were invited to Norwich to have dinner in the cavernous café of the Sainsbury Centre, with a host of other interesting people who Jago hoped might be useful collaborators in his project, hoping to make this remarkable collection of art and artefacts better known.

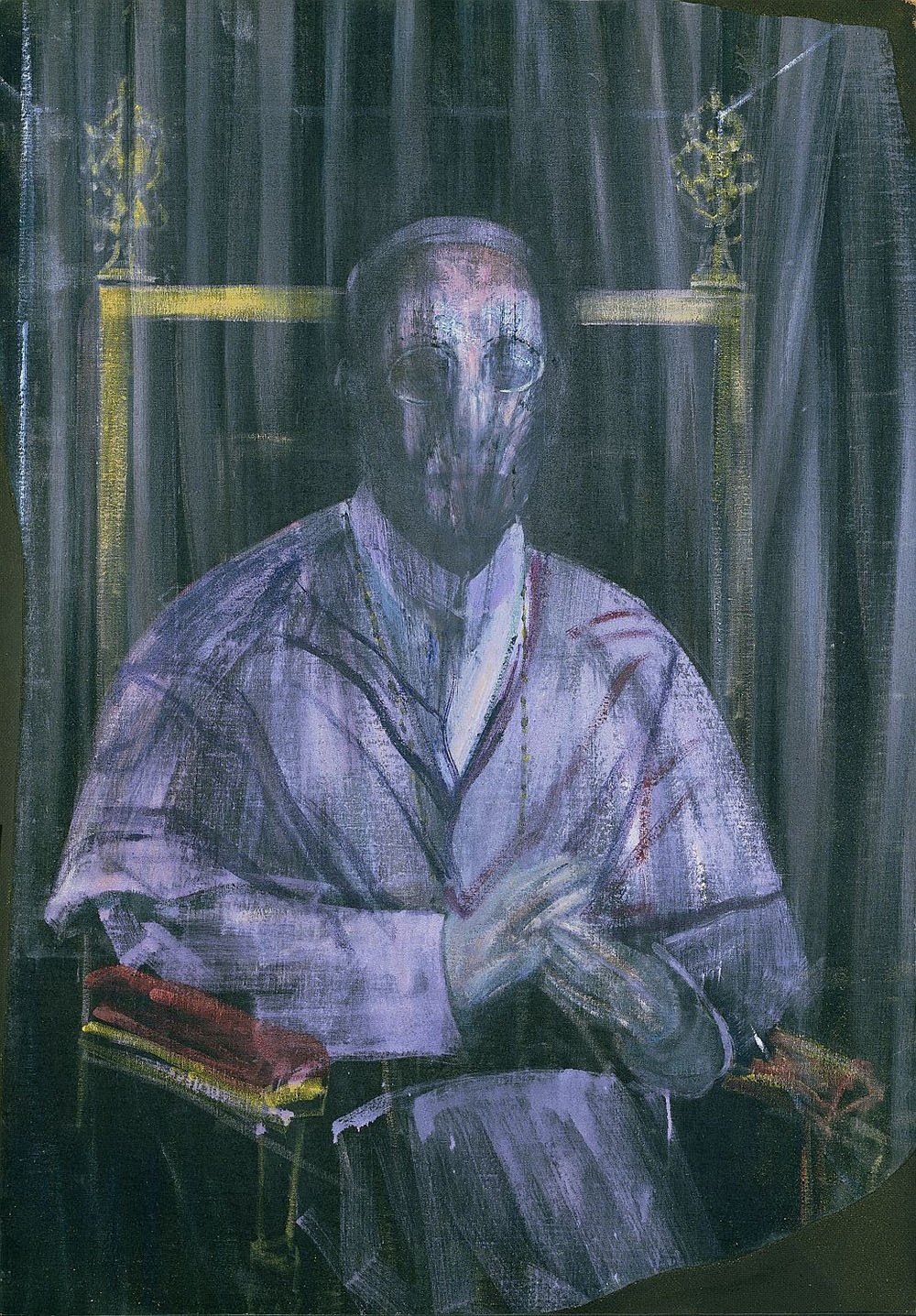

The collection began as the personal passion of Robert Sainsbury, scion of the supermarket dynasty, and eventually also that of his wife Lisa. An eclectic mix of ethnographic and cultural objects from every corner of the globe is combined with works by some of the most sought-after artists of the 20th century, big names from whom they bought works directly, and with whom they became good friends, like Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti. In the case of Francis Bacon, perhaps their closest collaborator, the couple were also the subject of many of the works.

When it became clear that the collection was too large and too valuable to remain in their London townhouse they began to search for a new home for it.

The morning after the dinner we returned to the museum to have a coffee with Jago, who sketched out the history of the Sainsburys gift. Their children were daunted by the prospect of inheriting this now considerable hoard of their parents accumulated artistic bric-a-brac and so enquiries began to find an accommodating institution. The Fitzwilliam in Cambridge proposed breaking it into more manageable chunks. They were happy to take some of the works and find homes elsewhere in the town for others, but they had no desire to clutter up their storeroom with works by Bacon, who wasn’t felt to be their kind of thing.

Unsurprisingly this was not how Bob and Lisa imagined their offer being received. The University of East Anglia in Norwich was the eventual beneficiary of Cambridge’s reticence. Already admired in architectural circles for Denys Lasden’s ‘ziggurat’ student accommodation, the University offered several acres in a corner of its estate to build a home for Bob and Lisa’s gift.

But who should they ask to design the building? Naturally they wanted something unconventional, challenging the idea of what an art gallery looked like. The choice fell on a little-known British architect who had lots of novel ideas, but at that point in his career had built very few buildings, and certainly no museums or art galleries. With the prospect of an open chequebook Norman Foster proposed an extraordinary high-ceilinged hanger, with a colossal central space to display the art, unimpeded by columns or other structural elements, where the collection could be seen in the round and would be constantly changing to ensure every object had its moment in the sun. The design was so simple it was difficult to believe it would stand up to the first windy Norfolk day. The end walls were formed from the largest sheets of plate glass that had ever been used in a British building, hung on an elegant but seemingly insubstantial superstructure of triangularly stressed steel columns. Everything necessary to provide for the needs of its occupants; the services, cables, pipework, loos, offices and a café kitchen, was cunningly concealed between the steel frame and the plate glass walls.

The Sainsburys loved it, and I do too. The simple form is beautiful, inside and out, and the art is a knock-out as well. I suspect Jago will be the perfect champion to guide it into its seventh decade but I’d best keep his plans a secret for now. It’s clearly going to be fun though!

As a painter currently working on a theme with lots of fabric I took a close look at this painting by Francis Bacon, Study (Imaginary Portrait of Pope Pius XII), one of his screaming Popes. The texture and shape of the papal robes are created with his characteristically dry brushwork, dragging the paint in vertical stripes across his chest. It almost feels like he doesn’t have enough paint to finish the picture but the marks are very effective, giving the cloth an almost translucent look. Sorry Francis, not impressed by the hands though.

Another picture that I lingered in front of was this portrait by Amedeo Modigliani of Anna Zoborowska, the wife of his dealer. In contrast to the Bacon the face is built up with mottled brushwork, carefully applied in progressively darkening shades to create a three-dimensional head. The drawn lines are interesting to me as they are not something I use in my own work, but here, as the catalogue says, ‘the artist attempted to convey as much as possible with the minimum of information’.