16 Oct ART HISTORY ROAD TRIP V: URBINO

The Ducal Palace, Urbino

‘Enthusiasts can take the trail to Sansepolcro and on, across the Mountains of the Moon, to see the sublime “Flagellation” in the Ducal Palace at Urbino, undoubtedly the greatest small picture in the world.’

– From ‘Summer’s Lease’ by John Mortimer, pub:1988, Viking.

I wrote last week of Aldous Huxley and his enthusiasm for The Resurrection, this week another English author is claiming global significance for a painting by Piero. The picture is The Flagellation and the author, the creator of Rumpole of the Bailey, barrister John Mortimer. Summer’s Lease is not a great book but when it was published we read it on a holiday in Tuscany, which probably accounts for our tolerance of this slight story of moneyed middle class Brits on holiday. It was actually Kenneth Clark who described the painting as the greatest small picture in the world, but this only serves to amplify the cultural aspirations of Mrs Pargeter, Mortimers heroine, who would certainly have watched ‘Civilisation’. The book lent the city of Urbino a mystical status and we were just as curious to see it as she was.

In 1925 Huxley complained that the bus from Sansepolcro to Urbino took seven hours and despite the greatly improved roads we still had a difficult drive. Setting the destination into Google Maps, the phone clicked home in its cradle and we set off. After roughly a minute the signal vaporised and so did any form of guidance.

We were going to cross the mountains of the moon with only the Italian road signs to help us.

Every peak presented a choice of route, traversing to the left or right, often with two signs pointing in opposite directions announcing the same destination and distance. However, all this paled into insignificance when we rounded the last corner and pulled into another colossal car park as, towering above us and glowing orange in the evening light was the breathtaking sight of the ducal palace of Urbino.

The Ducal Palace, Urbino

The town itself curved around the hilltop, beckoning us up with a variety of options; a lift, several staircases and a cobbled road that looked too steep for a car. We took the stairs and at the top found a piazza buzzing with activity, students and families out for dinner while the locals took a passeggiata. We had a plate of salami and cheese and a salad before wandering along the main street in the twilight.

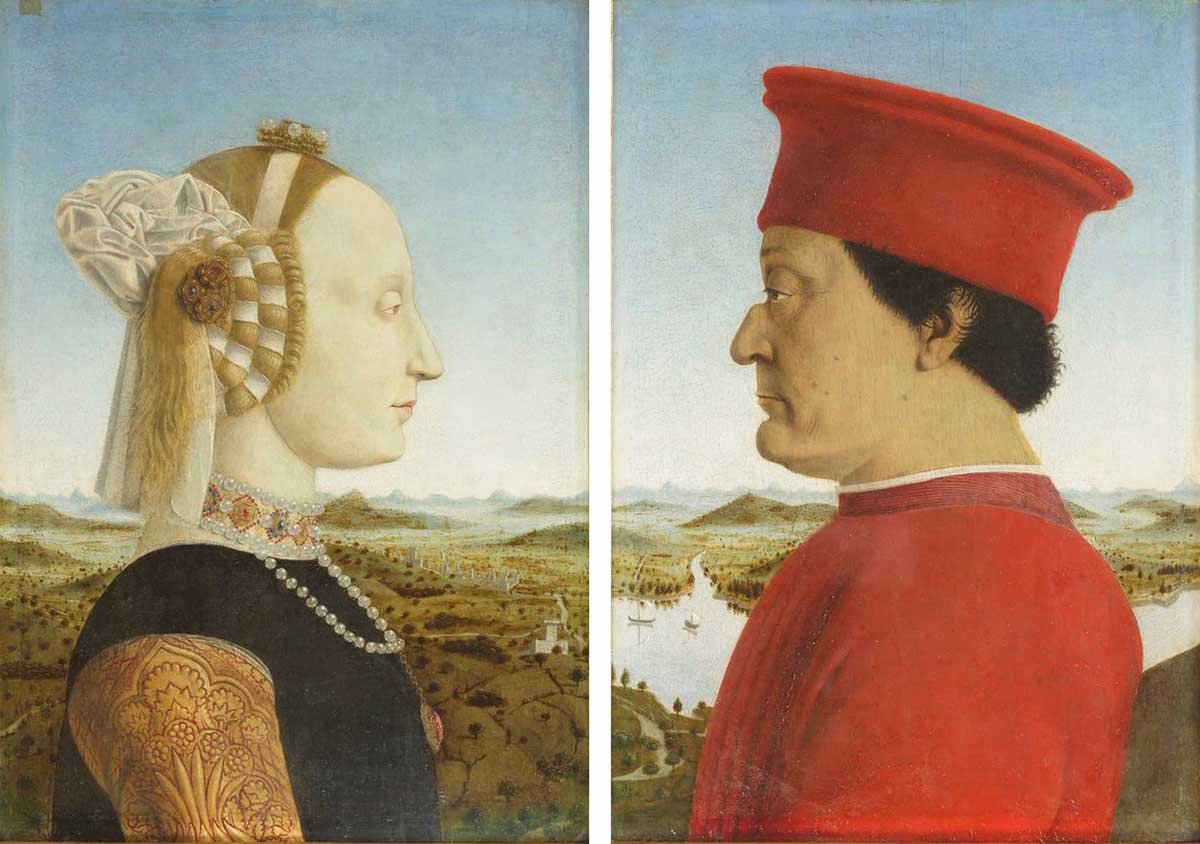

Diptych of Federico da Montefeltro and his wife, Battista, Piero della Francesca, 1475

The view up the hill in front of us is the conception of someone we met in Florence at the start of our trip; Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, whose double portrait with his wife, Battista Sforza, is described by its owners, the Uffizi gallery, as ‘one of the most celebrated portraits of the Italian Renaissance.’ The diptych, painted in the palace here in Urbino, has the feel of relaxed familiarity as Piero became a family friend and frequent visitor. Beyond his subjects is a landscape clearly meant to be the view from the palace, which the Uffizi blurb tells us ‘marries the strict approach to perspective learned during his Florentine education with the lenticular representation more characteristic of Flemish painting, achieving extraordinary results and unmatched originality.’

Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta

We passed the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta which Federico commissioned. It took over three hundred years to complete, suffering the setback of two devastating earthquakes in quick succession in 1781 and 1789. Next door was the main entrance to the great Ducal palace, barred and shuttered and brooding in the streetlight.

The next morning we were back at the open doors. The building seemed to have shrunk in the night and the object of our trip, Piero’s Flagellation was almost the first thing you see when entering. It doesn’t disappoint.

Flagellation, Piero della Francesca, c1450 – 1460

The scene is set outside, in a columned loggia. On the left a man is being whipped whilst on the right three men are in conversation. Piero has chosen to view the action from a low angle, giving himself a challenging job of foreshortening in the paved floor and making the three figures in the foreground seem huge.

The Flagellation of Christ, Caravaggio, 1607

Spike has a tendency to see all art in relation to Caravaggio, and recalls his vision of this scene, with sweaty muscular men exerting themselves in a dark dungeon. It couldn’t be more of a contrast to the tranquil serenity of Pieros painting.

There are perhaps a dozen theories that explain the setting of the picture and who the figures are meant to be. If you are interested they are listed on the painting’s Wikipedia page. Alternatively, there is an entertaining video primer on YouTube which unpacks most of these theories and explains the mathematical geometry of the picture in a very insightful way, links here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0UfYuhnBdb4

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flagellation_of_Christ_(Piero_della_Francesca)

Unsurprisingly I was drawn in by the clothes; the gold embroidered black outfit of the last character on the right and the super-cool man opposite him with his forked beard and black turban, his arms popping out of his cloak leaving the impossibly long sleeves hanging empty. The two groups are unfeasibly unaware of each other and the man with the whip and his fellow tormentors seem very lackadaisical at their work. There is no atmosphere of pain or violence.

Eventually we moved on, but the sense of unreality was disconcerting.

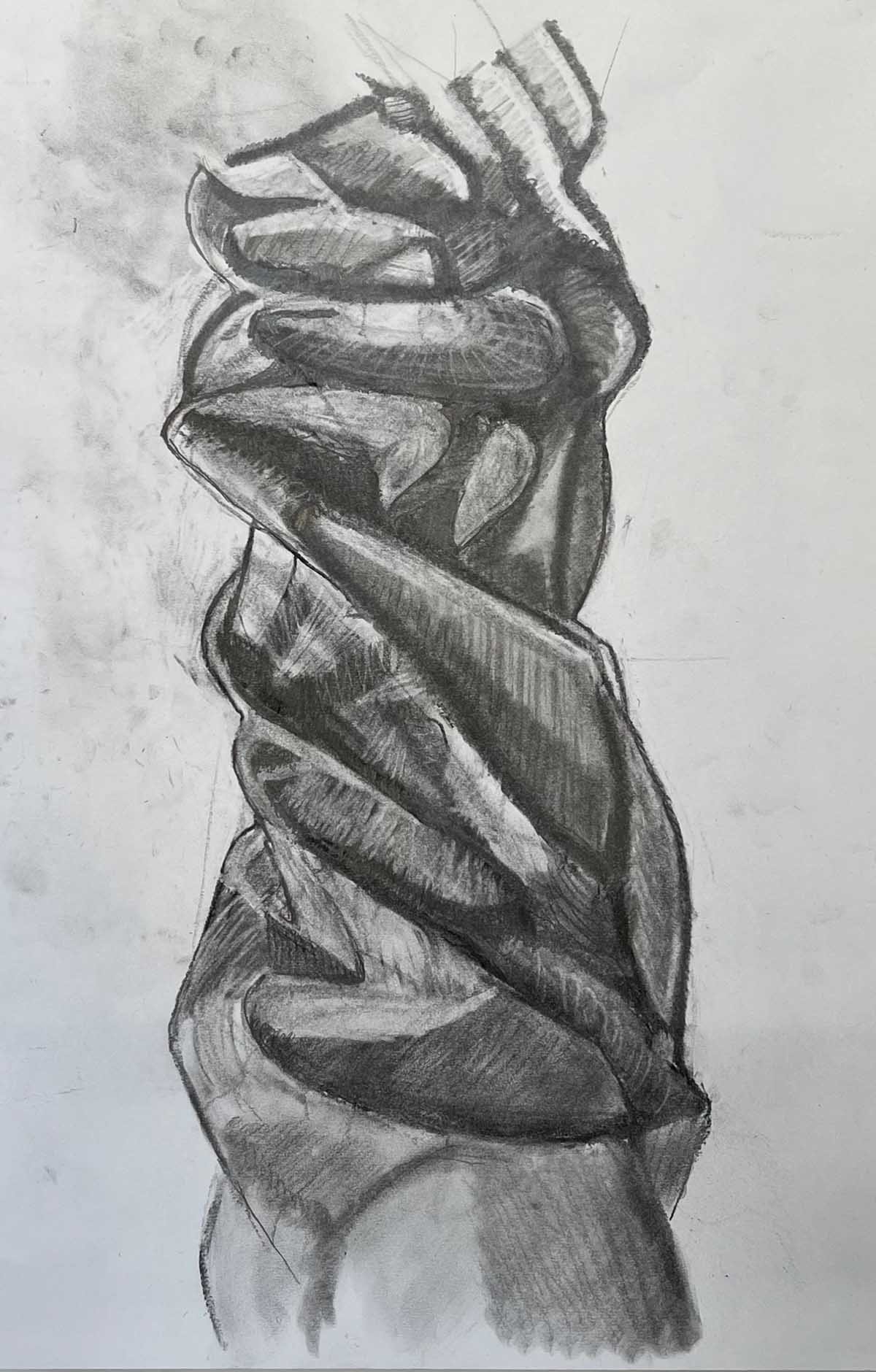

FOLD OF THE WEEK: THE SPIRAL

My drawing of a spiral fold

Renaissance painters employed the spiral fold to add movement and animation to a garment. It would guide the viewer’s attention across the picture, reinforcing the composition by leading the eye to key elements, bringing the figure to life with a dynamic and rhythmic quality. Spiral folds were used to enhance the curves of human anatomy, so celebrated and idealised by Renaissance humanists.

Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Raphael, 1507

Here is a great example of the spiral fold used by Raphael in his depiction of Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She turns her upper body in a contrapposto pose, her hand resting on a spiralling roll of ochre drapery which Raphael uses to create an elegant oval shape emphasising the curve of her body.

There are other important pictures that are worth a mention in the vast empty rooms of Urbino’s Ducal palace and next week we’ll try and squeeze them in before we hit the road home.

Have a great week.

Fiona