11 Nov Reclining

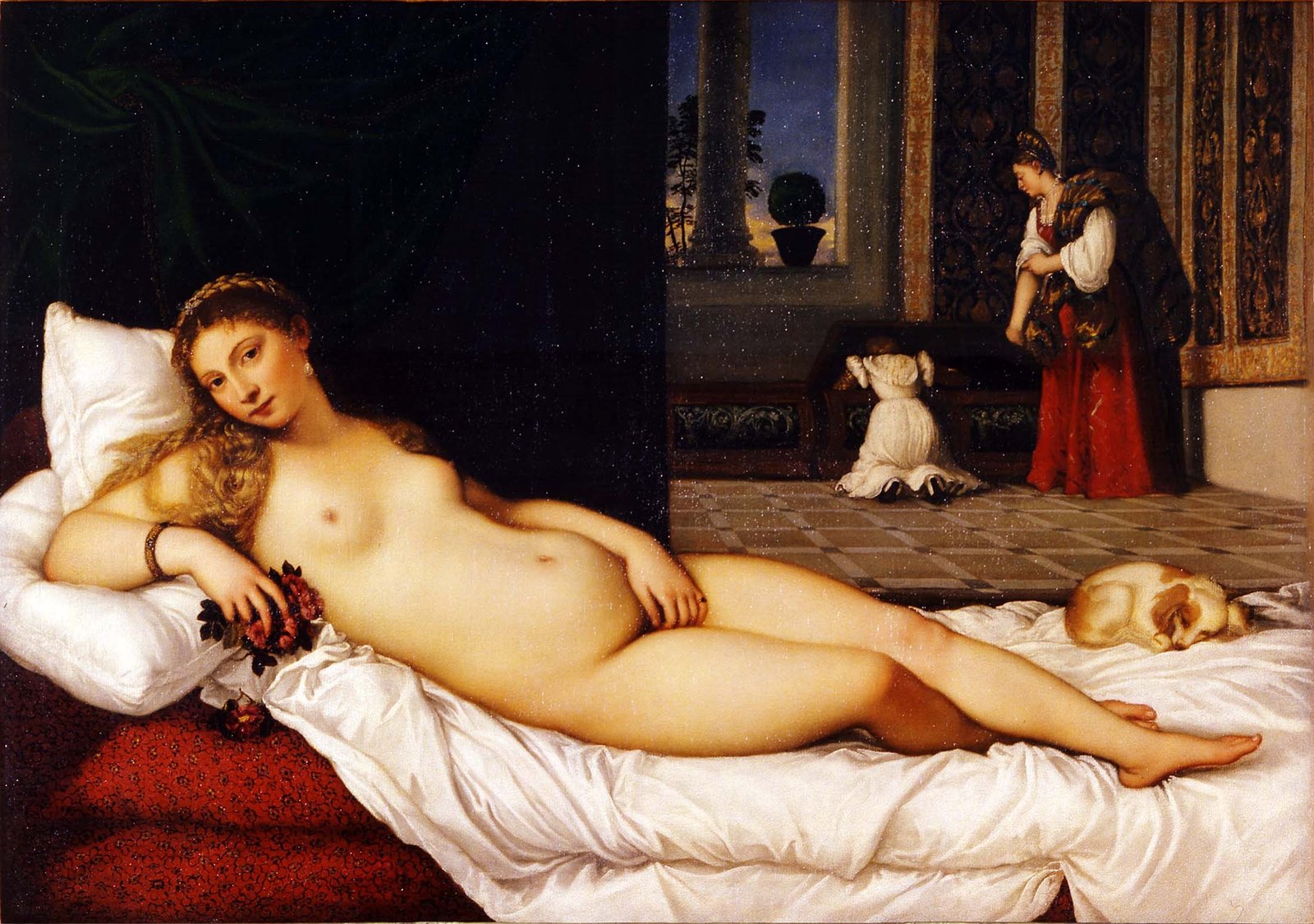

Venus of Urbino, Titian, 1538

After returning home from our northern Italian art history road trip we felt we owed ourselves some time to relax and recover and conveniently the theme this week is reclining. We left Urbino with Titian’s reclining nude, Venus of Urbino very much in mind, speculating on the mysterious setting with a maid seemingly putting the laundry away while another female figure looks on, but also on the significant effect the painting had on the history of art.

It was the prototype for a great many similar paintings as I was to discover during an online course run by the Royal Academy which I enjoyed hugely. Titian himself made several more pictures of women in repose, usually wearing very little, helping to make such subjects acceptable and even popular, but not much help for me in my quest to learn more about painting drapery.

The Rokeby Venus, Diego Velasquez, c. 1647-51

The Rokeby Venus

Departing from the full frontal version in the late 1640’s Diego Velasquez painted The Rokeby Venus from behind, her son Cupid holding a mirror in which she is still able to fix her gaze on the viewer. She is lying on a silk bed-spread exhibiting some good pipe folds which won my attention. The Spanish rather disapproved of female nakedness in art and the painting was kept in a succession of private collections until, in 1813 it was bought by an Englishman and hung in Rokeby Park in Yorkshire. It became widely admired in Britain when it was one of the works exhibited at the Great Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition in 1857, a seismic event in the history of British art that deserves to be better known.

Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester, 1857

Staged in a vast purpose built gallery in Old Trafford the show was an attempt to upstage the Great Exhibition and, artistically, it succeeded. It was undoubtedly the largest art exhibition in the world, a status which I would imagine still stands with 16,000 works on display. Key to the success of the exhibition, and perfectly exemplified by the Rokeby Venus, was the willingness of British aristocrats to lend the contents of their collections, previously hidden away in their grand houses. The purchases of generations of grand tourists were revealed to the public for the first time and it became clear that they had mostly bought wisely, albeit probably on the advice of canny dealers. The loan of these works meant it was possible to see a great many paintings and sculptures by the big names of the Renaissance and subsequent art movements without the necessity to travel to Europe which would have been beyond the means of most of the visitors.

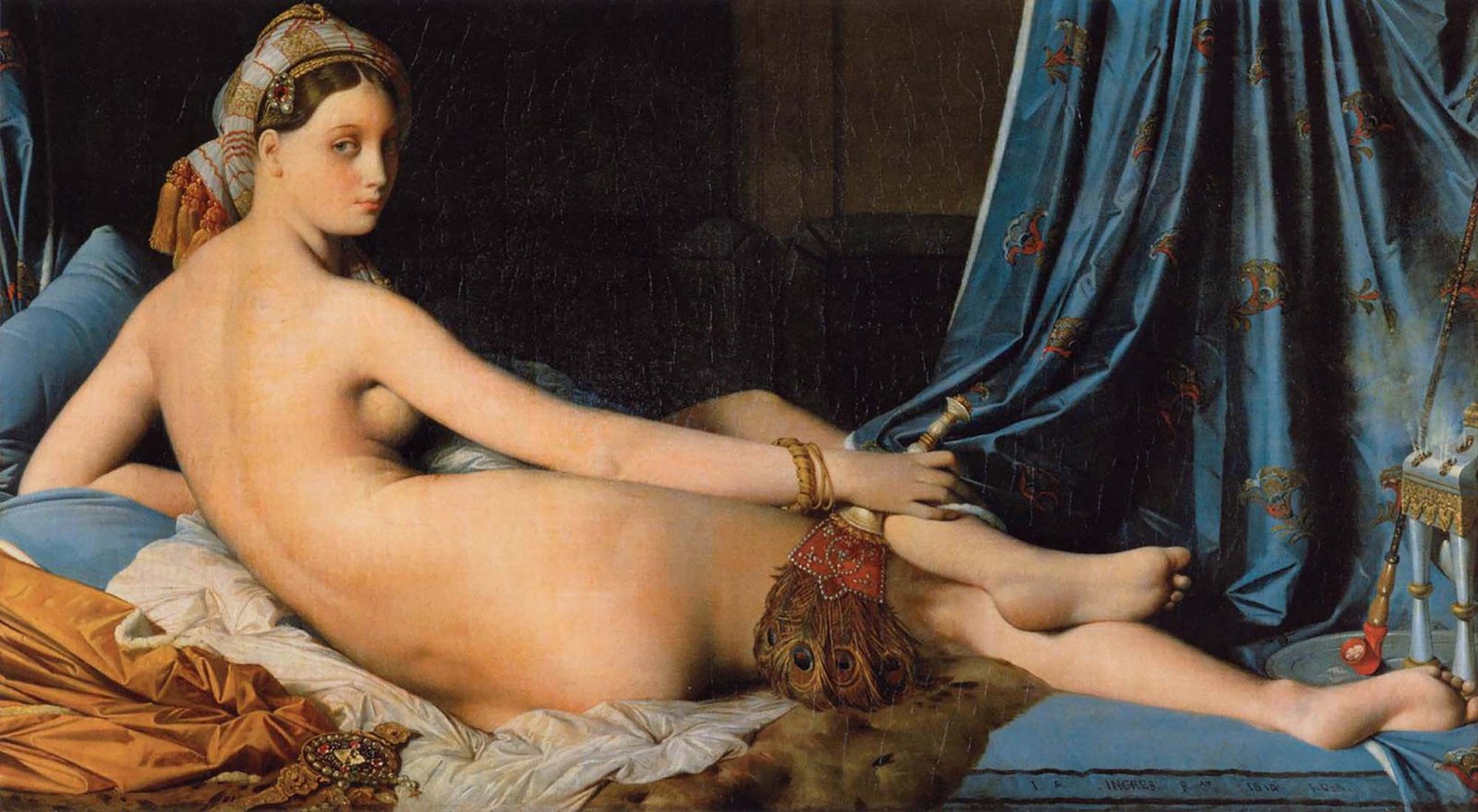

Grande Odalisque, Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, 1841

Grande Odalisque

The back view devised by Velasqez was used again in 1841 by Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, in a painting he called the Grande Odalisque. If, like me, you are wondering what an Odalisque is, I can help; it was a chambermaid in the seraglio of an Ottoman sultan. During the nineteenth century enthusiasm for ‘orientalism’ odalisque acquired a more suggestive air and was applied to court favourites, women who had caught the eye of the Sultan but had little to do while they waited to be summoned to the royal presence.

These women, usually pictured in a Turkish looking interior, were almost always languishing on a divan or bed, reclining but fully clothed in exotic costume.

Odalisque with fan, Hippolyte-Dominique Berteaux, 1876

I like this example, by Hippolyte-Dominique Berteaux and, as an exercise on the RA course, I made a copy using conté pencils. During the wars that followed the French Revolution the British prevented France from obtaining graphite from which the lead in pencils is made. M. Nicolas-Jacques Conté came to the rescue adding clay to graphite to make supplies last longer. I found the main difference is that the Conté is much harder to erase. Plan ahead!

Above is my copy of Hippolyte-Dominique Berteaux, 1876, Odalisque with fan, from my Royal Academy course.

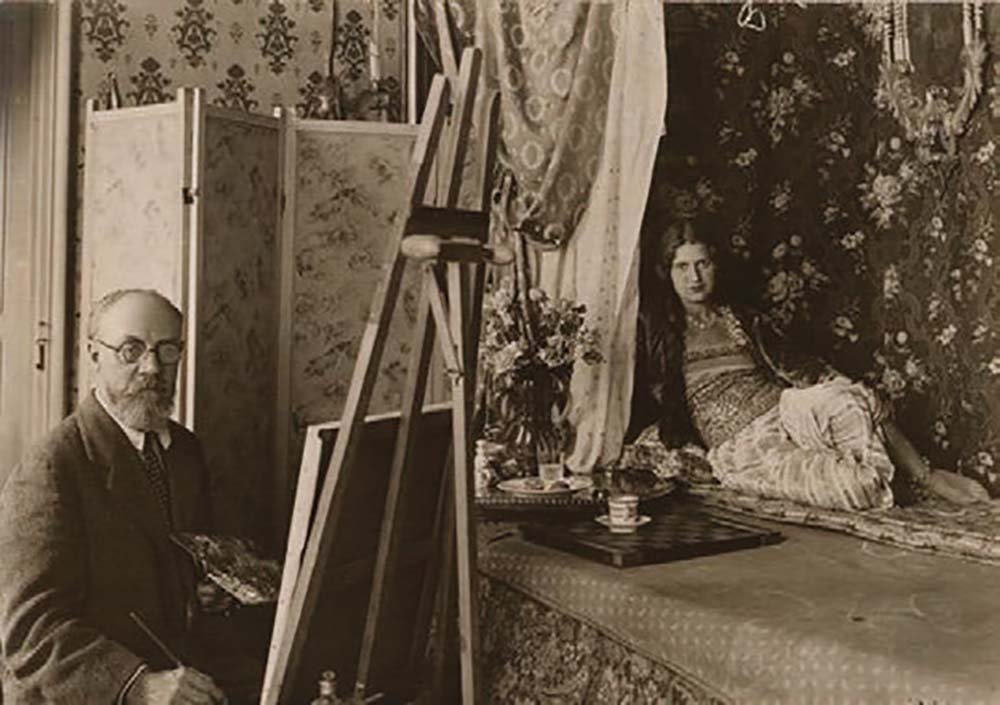

Matisse painting the model Zita at 1 Place Charles-Felix, Nice, 1928

Paintings of odalisques became something of a cliche by the end of the nineteenth century but in the years after the First World War the odalisque was given a new lease of life when Henri Matisse returned from a trip to Morocco fired with enthusiasm for the genre. We can save that story for another time but here he is in his home made seraglio in his apartment in Nice with his model ‘Zita’.

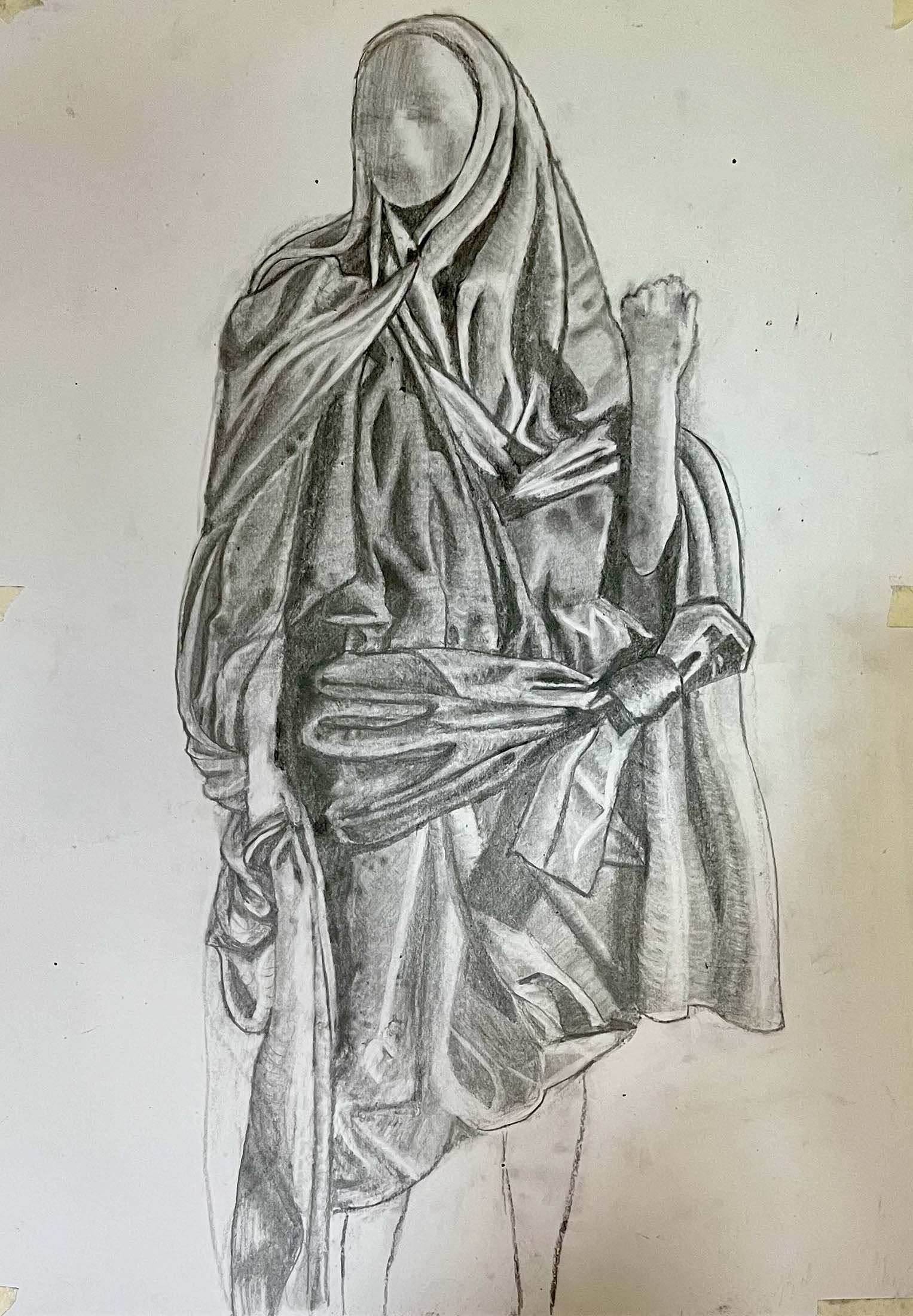

Fold of the Week: The Draped figure

Here, to conclude my New Masters Academy, Drapery course, I practised all of the folds; pipe, diaper, half-lock, zig zag, spiral and inert cloth in an extended drawing exercise with pieces of cloth draped and tied onto a mannequin.

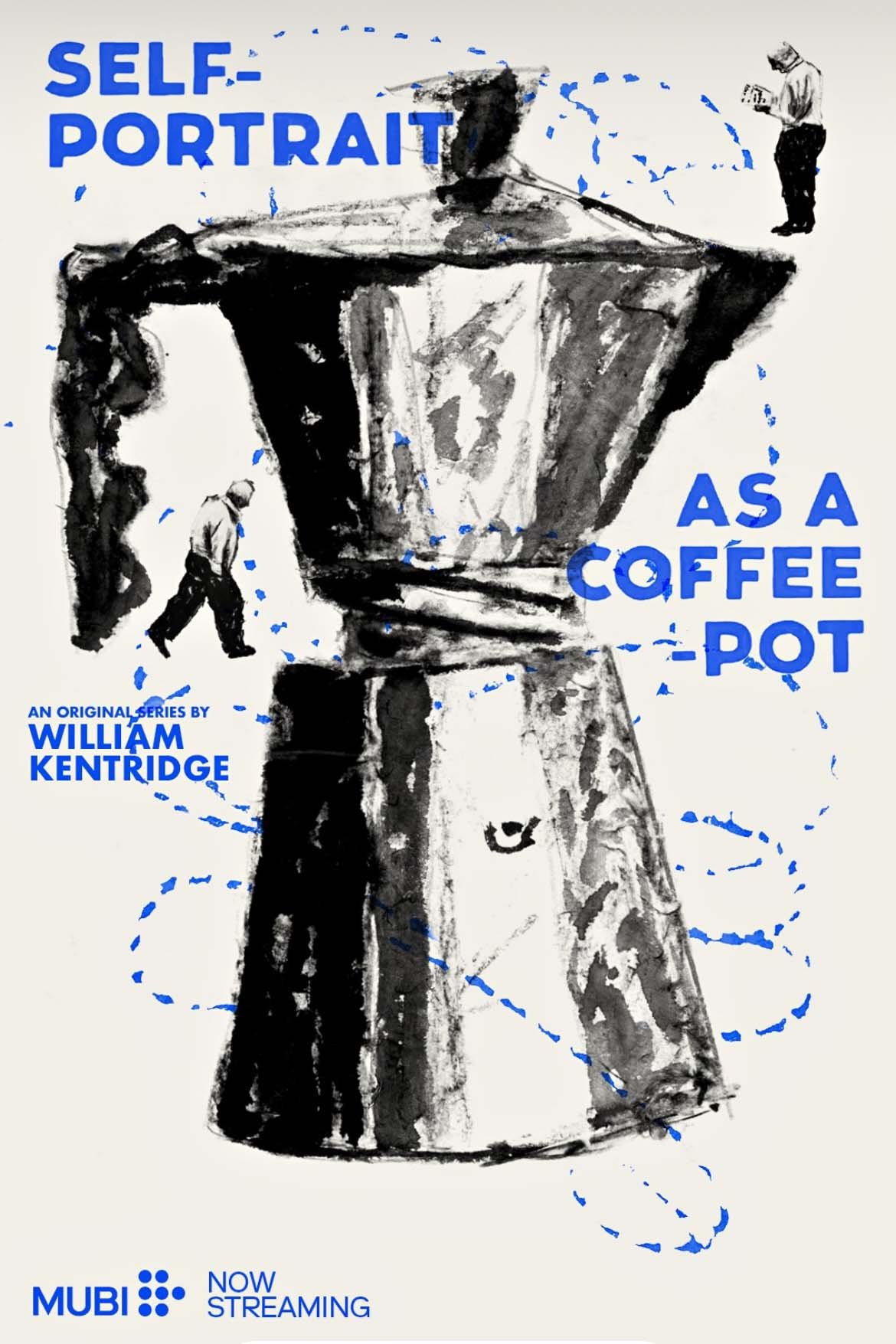

This week we have been enjoying the excellent William Kentridge, ‘Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot’, nine part series. If you sign up to Mubi you can have seven days viewing for free, enough time for us to squeeze them in before cancelling the contract.

I have been a fan of his for many years and he inspired many hand drawn charcoal animations, when I was studying drawing with Nick Bodimeade.

Have a good week.

Fiona